The Bottom is just the Top Again: Understanding overshoot in Sound system design

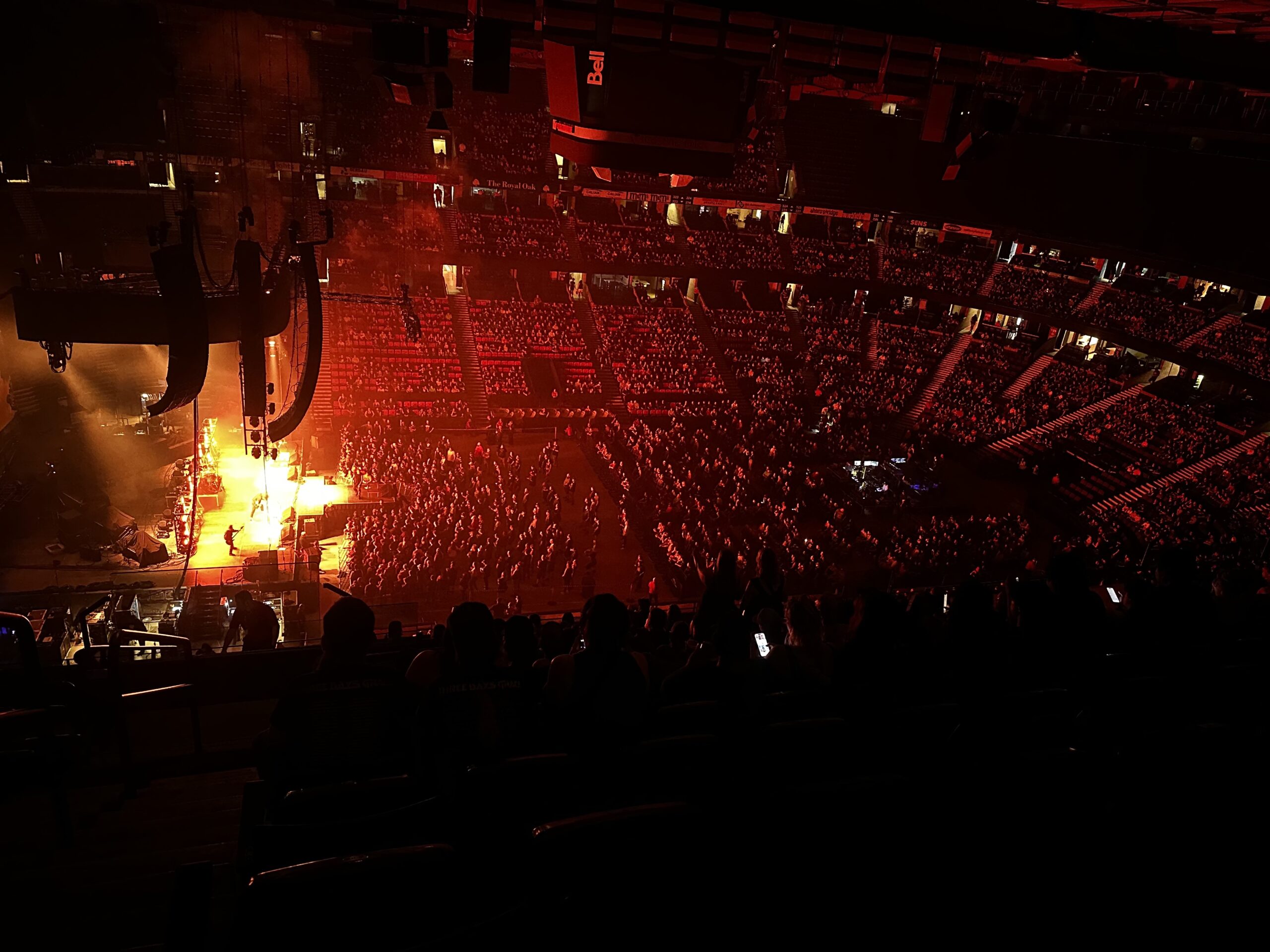

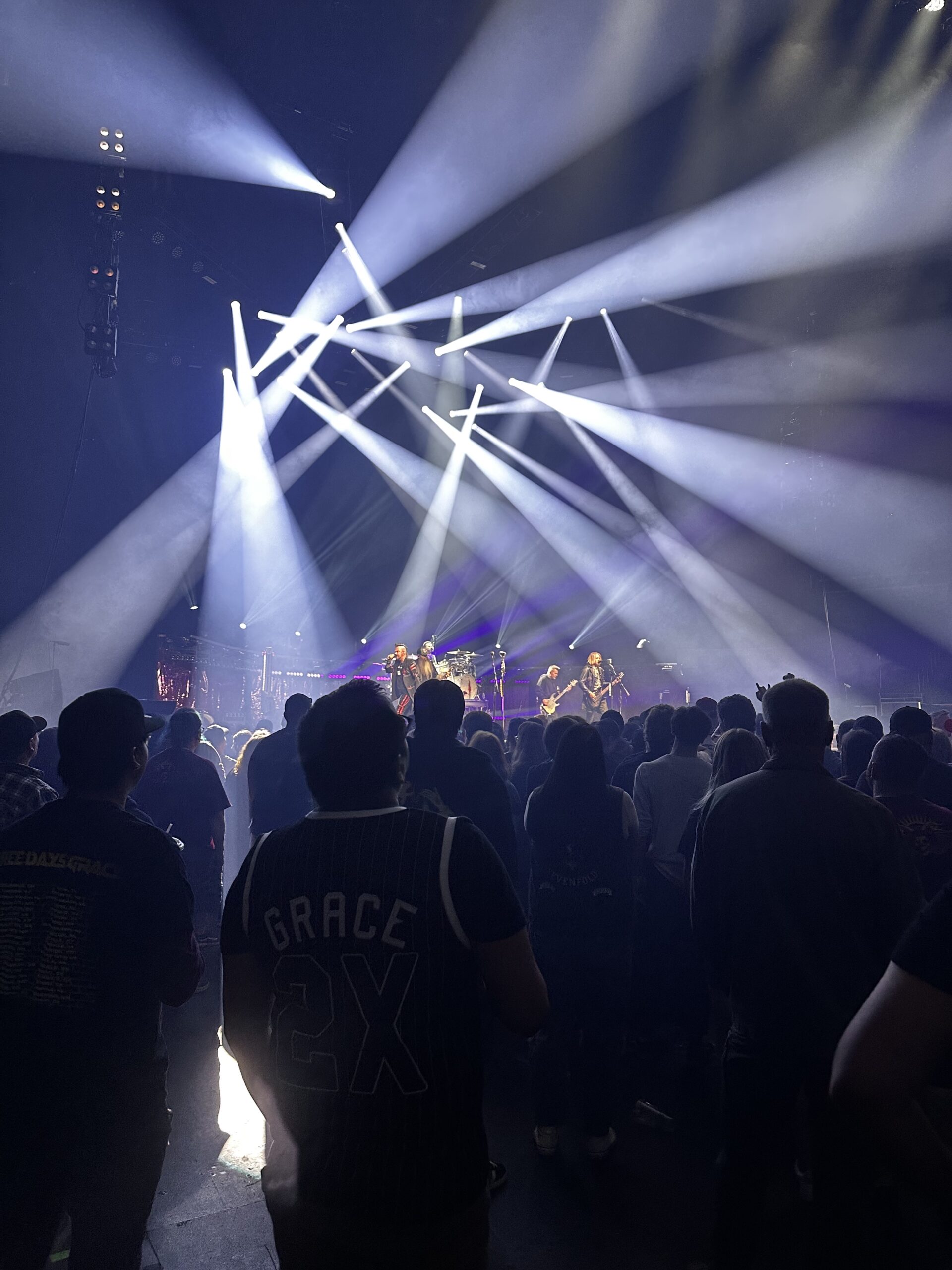

As a touring system engineer, the job encompasses many responsibilities—from managing the audio department and ensuring system consistency to collecting and interpreting acoustic data. Yet, I tend to believe that no amount of post-processing or tuning can fully correct a poorly designed or improperly deployed PA system. For that reason, I place strong emphasis on mechanical optimization: making sure that the physical deployment of the system is tailored to each day’s venue as precisely as possible.

When designing large-scale sound systems, particularly those using line arrays, there are a few foundational parameters we must account for: vertical coverage, horizontal coverage, and the uniformity of both. While these concepts are often discussed in terms of audience area coverage and array aiming, one design element that warrants closer attention is overshoot.

What is overshoot?

Overshoot refers to the intentional aiming of one or more loudspeaker elements beyond the defined audience plane—typically above the top row of seats or, in some cases, below the first row—depending on whether you’re applying overshoot to the top or bottom of the array.

At first glance, this may seem counterintuitive. Why aim a speaker where no one is listening? The answer lies in how line arrays interact with physical space and audience geometry, especially in terms of vertical coverage and high-frequency propagation.

Vertical coverage, smiles and frowns

In practical terms, line arrays project sound in a curved, multi-element pattern. These patterns can result in uneven distribution if not properly addressed. Industry terms like “smiles” and “frowns” describe vertical coverage anomalies:

- A smile is where SPL is louder at the top and bottom of a listening area, with a dip in the middle.

- A frown is the inverse—louder in the center, with a roll-off at the extremes.

Both are undesirable and can negatively affect intelligibility and tonal consistency.

Overshooting the top of the array can help mitigate these issues. By slightly extending coverage beyond the audience plane, you allow sound to “settle” more evenly over the listening area. It also improves high-frequency throw—especially helpful when working with tight splay angles and trying to reach distances upwards of 250 to 300 feet.

Strategic overshoot at the top of the array helps manage reflections off back walls and improve uniformity, but too much can introduce its own problems. Excessively directing sound into venue ceilings, catwalks, or metal roof structures can excite those surfaces, generating unwanted reverberation, comb filtering, or harmonic buildup. The result? A room that feels “live” in all the wrong ways.

As with most aspects of sound system design, balance is key.

What about the bottom?

Overshoot is traditionally considered in the context of the top of the array—but applying the same principle to the bottom can be just as powerful.

Rather than aiming the bottom cabinet directly at the front row or the feet of the audience in the pit, consider targeting a point just inside the barricade or even slightly downstage. Doing so can dramatically improve coverage in the high-impact front rows area and reduce reliance on underpowered or under-specced front fill systems.

With this approach, your front fills can shift from being a crutch to a strategic localization tool, enhancing the imaging of a system pulling it down towards the stage rather than merely filling gaps in coverage. The result is a more consistent experience across the first few rows—an area that can be often underserved or at least undercovered.

When overshoot becomes overkill

As with overshooting at the top, too much overshoot on the bottom can introduce new issues. Directing significant energy into the stage surface can lead to excessive bleed into open microphones, increasing the risk of feedback—particularly with sensitive sources like string sections, acoustic instruments, or lavalier mics.

The key is subtlety: small adjustments in tilt, coverage area, and focus can yield large improvements without overloading the system or space.

In Summary

Overshoot is a powerful yet often underutilized design tool in large-scale concert sound reinforcement. When used intentionally and judiciously, it allows system engineers to mechanically optimize vertical coverage, and achieve greater consistency throughout the venue.

By understanding the acoustic behaviors behind sound systems and the use of overshoot—we gain another valuable method for elevating the audience experience.

Whether it’s aimed above the top row or below the barricade, remember: sometimes the bottom is just the top again.